The Family That Screams Together *Can* Stay Together

by Teena Apeles

Google Search

There is no shortage of articles discouraging constant screaming (or raising one’s voice) in relationships, especially when parenting. We all scream, of course. Why? In a TIME article from 2015 on scream science, the reporter writes, “Screaming serves not only to convey danger but also to induce fear in the listener and heighten awareness for both screamer and listener to respond to their environment.” This we already know. What most of us do care about is when that practice is considered acceptable, normal, or actually abusive behavior. (No one can excuse the latter.) Though it isn’t fair to judge other’s personal relationships without taking into account the context and people involved. Cultural norms vary; what’s considered screaming versus talking loudly, or dare I use the word healthy communication, in one household can be completely out of sync with another’s. Some obviously may gasp at the thought of familial relationships surviving and thriving when a household’s volume is often high, but to them, I say, “Ours has!”

My own memories of childhood and my current interactions with my parents are, well, pretty loud. I’ve heard my dad say on a number of occasions to my two sisters, my mom, and me when we’ve called out his volume, “I’m not screaming, this is the way I talk.” I should note that we are a no-filter kind of family: We speak our mind in the moment—which can take some people by surprise (our respective partners are still are coping decades later with this), while others find it refreshing. Our interactions are very animated. I’d say silence is actually the most uncomfortable volume in my life. Our Filipino American household was constantly filled with noise, as were our extended family’s homes: loud music, singing, TV, food being prepared, late-night activities, and yes, squabbles.

From infancy to our early elementary years, my sisters and I spent most of our time at my lolo and lola’s (grandparents’) house, which was also a daycare, where we were joined by the often-deafening noise of our many cousins’ and other kids’ screams and hijinks. We had the freedom to make as much noise as we wanted as our Manang Mary, our nanny/second mom (who also raised my dad and his six siblings), cared for all of us while watching women’s wrestling, in between feeding, cleaning, disciplining, and loving us. We screamed, we fought, we explored, we lived. I couldn’t imagine it any other way. That daycare was loud with laughter and scolding, and after-daycare hours were equally noisy: the sounds of four to five tables of mahjong being played simultaneously—marked with dramatic shouting matches by our lolo and lola’s Filipino senior-citizen friends and the sounds of their tiles being thrown, shuffled, and slammed onto the table. We reveled in it.

“a cacophony of constant noise is still my normal. and I like it that way.”

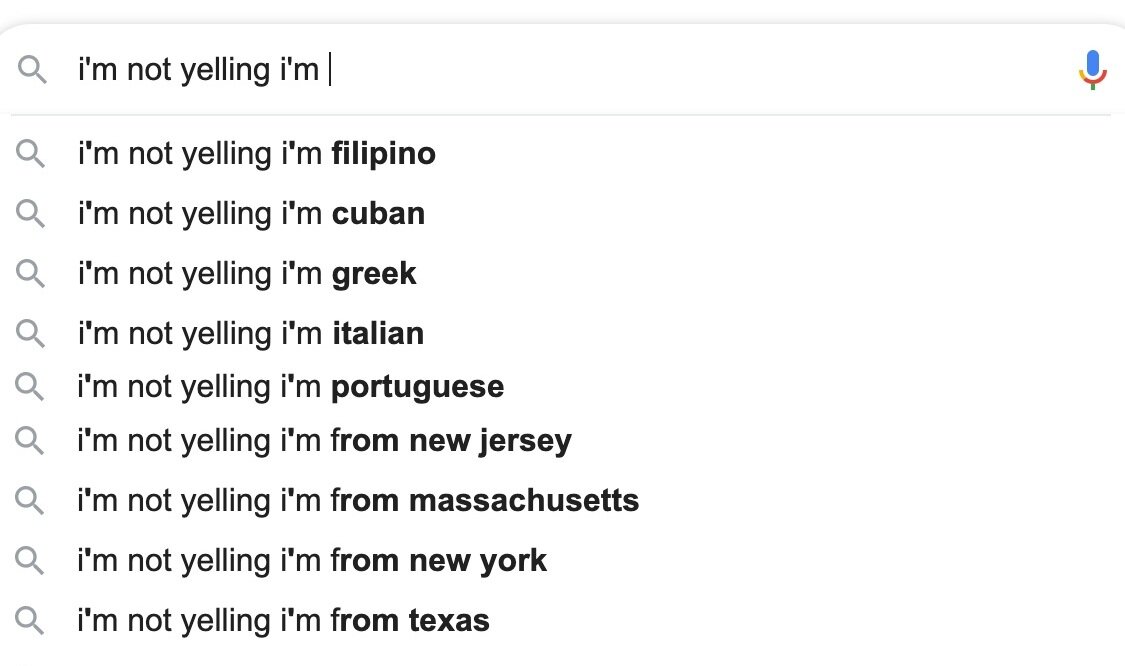

A cacophony of constant noise is still my normal. And I like it that way (except when I’m writing). I can look to my parents, two years shy of their 50th wedding anniversary—and our immediate family that is as tight as one can be—as a normal that lasts. Apparently, yelling is perceived as so common in our culture that the saying “I’m Not Yelling, I’m Filipino” and variations on it are available on all sorts of merchandise, as with other cultural groups if you just Google those first words. According to popular search terms, Italian, Polish, Italian, Greek, and Hispanic people and Texas, Wisconsin, and Chicago girls can relate.

Only now as a parent have I ever felt a need to explain why my family speaks to each other loudly, because people are so quick to counsel new parents how to properly raise and talk to children. I’ve seen how other mothers speak to their kids, in, you know, that way child psychiatrists and parenting columnists would approve of. Sometimes seeing them makes me cringe, because I couldn’t even imagine or want that. It just wouldn’t work in my family.

My own seven-year-old daughter, who is much more mature than I am (old soul, she is), actually giggles when I try speaking to her in soft tones. She’s well aware of the normal volume of her extended family, especially as the older generations are losing their hearing—too stubborn to use hearing aids. She also realizes that she’s only okay with us communicating that way. At school, she and her other friends kept gushing over their 1st grade teacher because “she never raises her voice.” Previous teachers or caregivers did scream at them; it became their normal. When they finally experienced what a year was like with someone who did not yell, they realized it could be a reality, and they like it. “But not at home, Mama,” my kid says to me. “I like us how we are.”

A lifelong friend of mine who is a psychiatrist acknowledged that while yelling was not the norm in his family, there are factors that shape what speaking volume is okay in another’s: “Since I was not raised in that manner, high volumes are off-putting to me. Actually, there were some extremely loud arguments between my two parents as well as between my older brother and my parents when I was young, and that was very scary,” he said. “However, I do think this is very much culturally determined, and that in some cultures, it is the norm and not necessarily harmful, or not as harmful as those not of those cultures might jump to conclude.”

Apart from just attributing our speaking loudly to our cultural background—maybe I should just say my and my parents’ volume (just yesterday my older sister told me, “Why do you have to be so loud?”)—I can identify other factors that contributed to the increasing volume of our interactions. For one, I can just look to the size of our homes. When we moved from modest, single-story homes into split-level and later two-story homes, my family’s volume definitely grew with our square footage (along with our laziness). Plus, in a family of five, there’s competition there. We screamed to be heard, we screamed because it felt good to scream, we screamed because that’s what it took to overcome more walls, more stories, and all the other noise: my dad’s karaoke system, blasting TV news, spirited phone conversations, family or friends visiting.

Many of my friends during high school had equally loud households, many of whom came from, coincidentally, immigrant families as well: Mexican, Persian, Irish, Hungarian, and Japanese. I should also acknowledge that my sisters, our friends, and I started raising our voices more as we got older—especially to our moms and each other. Perhaps this was just typical teenage-girl behavior. Blood pressure was raised often.

Letting emotions out in the most primal way may not be the most effective way to calm tension for everyone, nor is it always beneficial to both parties, but communication in loud voices doesn’t always mean destruction. As a parent now, I see my own volume getting higher as my daughter becomes more combative; she’s testing her limits as am I. I’m not proud when I’ve gone too far with screaming out of frustration when this little person ignores me. There’s so much sacrifice that she as a child has failed to see, and I understand now why my parents yell at each other and us—still. It’s bonded us in a weird way, but torn other families apart. Not everyone can live like this or should. Our heightened communication works for us, because we all participate in it. We scream together. And when people want us (me and my parents) to turn it down we turn it up. So mature, right? But I know we’re doing well. We are solid. We lash out and then the conflict is over.

“communication in loud voices doesn’t always mean destruction.”

As I told colleagues, family, and friends about this piece, I was pleased to find quite a few who totally got it. Valentina Quezada, who has produced youth and family programming at Los Angeles–area art museums, is from Ukraine, and whose son just turned one, was one of them. “Initially I found the title very funny and felt a strong connection to it. It brought up instant memories of growing up in a Russian-speaking, matriarchal household, where yelling was not a sign of anger, but rather a normal way of communication,” she shared by email. “I am a naturally loud person (which has on occasion gotten me into trouble). Growing up, the volume in the house was always loud, because we were trying to talk over the TV, which my mom never turned off. It took me a while to get used to not competing with the sound of the television after I moved out of my parent’s house and didn’t have it on all the time. My in-laws are also a loud family and they have TV on at a high volume.”

Quezada, like me, has seen how the volume of her interactions with her son has changed: “After having a child, I tried making a conscious effort to speak more softly and encouraging others around me to do the same,” she recalled. “But I am noticing, as he gets older, I have been moving back to my normal volume of speech and caring less about the noise of the television. You have to pick your battles with family!”

She added that her occupation has shaped her behavior as well, “I was actually pretty shy growing up and didn’t necessarily speak up in social situations, like with friends or at school. I really found my voice later, particularly when I began teaching. The voice of my grandmother resonated with me, and I often echoed it when trying to tame an unruly group of children.”

What some children from immigrant families often have to confront, especially when they are in areas where they are in the minority, is what we once thought of as normal shifts when confronted with others’ households. It can be confusing. “I am pretty comfortable with raised voices and often don’t even notice. My husband, on the other hand, will often point out when my family is getting too loud, and he isn’t sure if we are arguing or not,” shared Quezada. “Being loud definitely gets a bad rap, because I think it is mainly associated with ethnic cultures. Growing up, my ‘American’ (aka Caucasian) friends always had nice and quiet homes. It was only when I was around families of other cultural backgrounds that I felt at home and that things were ‘normal.’”

In the house I live in now, actually my childhood home, one of my most vivid memories here isn’t a visual one, it’s an auditory one: my father and my lola (my mom’s mom) screaming at each other in Tagalog. I wasn’t damaged by it. I don’t know if my mom was, but we survived it. I knew there would be some resolution after, we’d all still be together. There was never a doubt in my mind.

I think that therein lies the difference. My family screams at each other because we know our relationships will endure it—because no one is leaving each other. My sisters and I are closer than ever as adults and to our parents. My dad’s adult outbursts and my mom’s may be unusual (or deemed unhealthy) to some, but they come with five decades of love. At dinner the other night, he even said (in an unusually soft tone), “Yes, dear, we scream, but what matters is that we’re still together, and we have our health.”

They have lasted. We will last . . . expressing our love, togetherness, loudly.

Teena Apeles is a writer, book editor, and mother to a prolific maker. She founded the LA-based creative collective, Narrated Objects, which produces books and events to support causes close to their hearts. You can find more of her articles here.