These “4 Horsemen” Can Predict Which Couples Get Divorced

by Marissa Pomerance

There are 4 things that some couples do regularly that are so unhealthy, they’ve been dubbed “The 4 Horsemen,” as in, the 4 horsemen of the apocalypse, according to The Gottman Institute.

And how does this one institute get to make such bold assertions, you ask? Well, Gottman Institute founder, Dr. John Gottman, is known to predict which couples will get divorced with over 90% accuracy. Sooooo we’re inclined to listen to him.

And why THESE particular horsemen? Why not cheating or lying or clinging or neediness? Well, “these 4 things are predictive of divorce because they each indicate disconnection and opposition in communication. Rather than expressing their emotions and needs, the couple is engaging in unhealthy patterns which disrupt their ability to connect and thrive,” says Hanna Stensby, a Gottman Institute trained marriage and family therapist from Couples Learn Therapy.

Without further ado, here are those 4 horsemen to watch out for, along with the “antidotes” for solving them.

1. Criticism

If we are frequently criticizing our partners, that’s not a great sign.

Criticism isn’t just a mild complaint or critique— “this is not just talking about an action that someone did or expressing a feeling, but talking about that person’s personality or character as flawed,” says Stensby. This type of criticism leaves partners feeling attacked, spurned, and wounded.

These criticisms usually take the form of “you” statements, like, “you never listen to me,” “you never pitch in around the house,” and “you always get to be the ‘fun’ parent.’”

Often, underneath this criticism, is a personal need—we need our partner to listen more, we need them to take on more responsibility, we need to not have to nag them to do the dishes. And when those needs aren’t met, we feel bitter and hold grudges. “Criticism can also arise out of a lack of self-compassion and self-confidence in the criticizer, or as a response to a partner who is emotionally disengaged or shut down,” Stensby explains.

This criticism can escalate when each partner starts criticizing one another more frequently and intensely, as a way to get back at the other for their harsh criticisms, encouraging an unhealthy pattern of one-upmanship.

The Antidote:

According to Gottman, “the antidote to criticism is to complain without blame,” which means gently expressing our own needs using “I” statements, and not resorting to blameful “you” statements.

Here’s a helpful guideline—if we’re trying to address a problem with our partner, we should think of these two questions before speaking:

“What emotions do I feel?”

“What do I need from my partner in this situation?”

Examining our own emotions and needs allow us to reframe the problem to be about us, instead of our partner’s flaws.

Here’s an example of a criticism, and then how to reframe that criticism to be a positive, “I” statement:

Criticism: “You know the kids aren’t allowed to use the iPad unless they’ve finished all of their homework. You always let them do whatever they want!”

The antidote: “The kids are using their iPads but haven’t finished their homework yet. I need your help to make sure they follow this rule.”

Giving our partner the opportunity to “repair” the problem, without blaming them for it, is a healthier, more productive approach to managing conflict. When we shift from blaming statements to ones focused on our own needs and finding mutual solutions, we also ward off the other horsemen, like contempt and defensiveness, by nipping them in the bud.

2. Contempt

This is a BIG one. The biggest predictor of divorce out of all the horsemen. Contempt.

Of course, none of us think we actively display contempt to our partners. We love them! That’s why we decided to spend our lives with them, right? But anyone who’s married knows that love and hate aren’t always conflicting emotions.

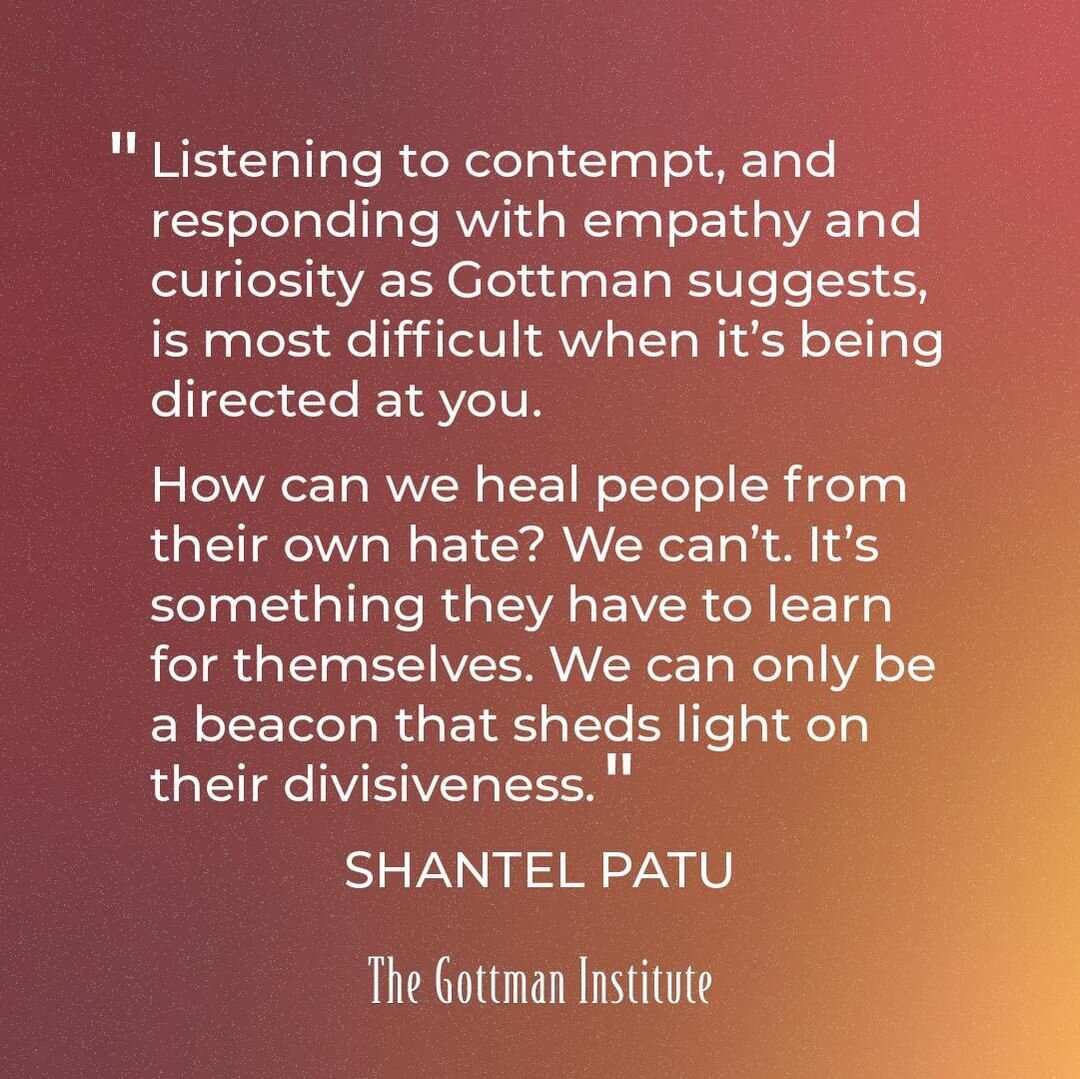

Contempt doesn’t necessarily look like hatred—it can look like meanness and mocking and condescension and sarcasm. Rolling eyes, sneering, and name-calling are all also forms of contempt.

Because while criticism might signal a bottled-up frustration or unmet need, contempt signals long-term disdain for a partner. “Overtime, if we don’t voice our own needs, we can build up feelings of resentment. Additionally, when we feel unappreciated, we can feel resentment. These feelings of resentment, if directed towards our partner, can become contempt,” says Stensby.

The most dangerous part about this pent-up resentment and contempt? It negates the respect and admiration we have for our partner. “Our ability for appreciating our partner becomes diminished by repetition of not getting our needs met or feeling unappreciated,” says Stensby. “As a result, we resort to criticizing our partner and then putting ourselves on a moral high ground by claiming to be smarter, kinder, cleaner, etc. than them.”

Using our above example, here’s a quick reminder of what criticism might look like:

“You know the kids aren’t allowed to use the iPad unless they’ve finished all of their homework. You always let them do whatever they want!”

And here’s what the contempt version looks like:

“God, it’s like you don’t even know how to parent. Do you SEE the kids using their iPads? Have they even finished their homework yet, or do you just not care anymore? It’s like I have to be YOUR parent, too!”

Contempt is so dangerous, that couples who show contempt are more likely to suffer from illness, according to Gottman’s research. Yikes.

The Antidote:

Contempt can be a hard one to shake, especially because the antidote seems simple, but really, mastering it is at the crux of any healthy relationship.

The short-term antidote to contempt is to “describe your feelings and needs.” This is an in-the-moment solution, similar to the antidote for criticism.

It means switching your communication to productive, positive “I” statements, like:

“I need more help with the kids, and I need us to be on the same page about how they’re following our rules.”

But the long-term solution is harder and much more important. It requires building “a culture of fondness and admiration” in one’s relationship. This takes time, often starts small, and requires a sustained effort over time. According to Stensby, “by voicing our needs and talking about our own feelings to our partners, we will reduce resentment. Also, it is important to voice appreciation and compliments towards our partners, and to hold that in our awareness when we feel frustrated, so that we continue to view them in a positive light. By creating a practice of appreciation for our partners, we will dismantle contempt within the relationship.”

To reduce contempt, Gottman also recommends doing “small, positive things for your partner every day” as a way to start.

Learning how to tamp down contempt might be especially tough for people who are sarcastic or like to tease. We might need to take a harder look at whether our “jokes” are actually funny, or if they’re truly hurtful and harboring deep-seated resentment, which means “having conversations with people about how they receive these jokes,” explains Stensby. “Notice if the jokes are landing, or if people seem hurt afterwards.” And when in doubt, “never joke about someone’s character. If the joke is at the expense of another person, is it really fun? You can still poke fun at something without putting others down,” she says.

3. Defensiveness

Defensiveness is the third horseman, and it often coincides with criticism.

“If we feel as if we are often ‘in trouble,’ or trying to find a way to discharge the difficult emotion of shame, we may be acting defensively. If we notice that we respond to feedback with an excuse, an attack on the other person, or some resistance to accept responsibility, then we are being defensive,” explains Stensby.

None of us like feeling attacked or rejected or criticized. But a defensive reaction can be damaging, too.

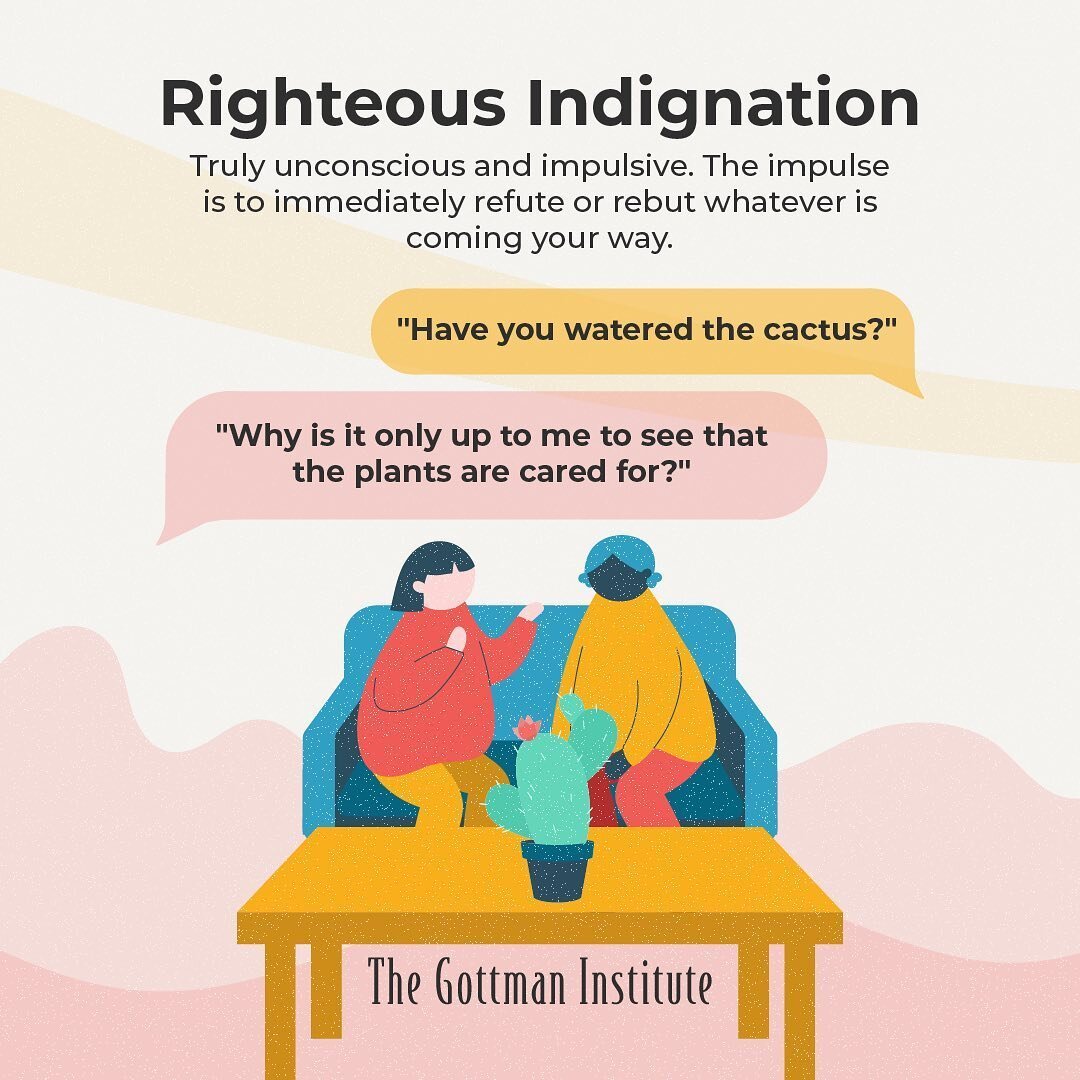

Why? Because it means that we’re unwilling to recognize or admit to our own flaws. And instead of copping to our shortcomings, we invoke “righteous indignation” or “innocent victimhood” to flip the criticism back on our partner as a form of self-protection. We make it their fault, so that it’s never ours.

Here’s an example:

Partner 1: Did you pay the mortgage this month? If we don’t pay it on time, we get charged a big late fee.

Defensive Partner: How am I supposed to remember to pay ALL of our bills when I’m also in charge of the kids’ schooling AND cooking AND cleaning? It’s YOUR job to remind me, and if you don’t, then it’s your fault if we get a late fee, not mine.

Defensiveness causes conflict to escalate because, instead of absorbing a complaint, we turn it into a new criticism of our partner, leading to a cycle of criticism that can lead to contempt.

The Antidote:

According to Gottman, this one’s pretty clear—“take responsibility.” We cannot begin to mitigate conflict unless both partners take responsibility for their part.

To do this, “we can ask the people close to us if they experience our defensiveness...but must be willing to hear what they are saying. By having self compassion, it will allow us to be more comfortable with owning our mistakes rather than being defensive,” explains Stensby.

Here’s an example of that same discussion, but with responsibility instead of defensiveness:

Partner 1: Did you pay the mortgage this month? If we don’t pay it on time, we get charged a big late fee.

Defensive Partner: Oops, I forgot. I’m so sorry. I’m going to pay it ASAP and set reminders on my calendar so I don’t forget again.

This means that we’re acknowledging our own shortcomings while showing a genuine concern for our partner’s feelings, and becoming better problem-solvers since we’re less resistant to change. For a healthy relationship, both partners need to be able to do this, otherwise, the fault will always fall on one partner’s shoulders.

4. Stonewalling

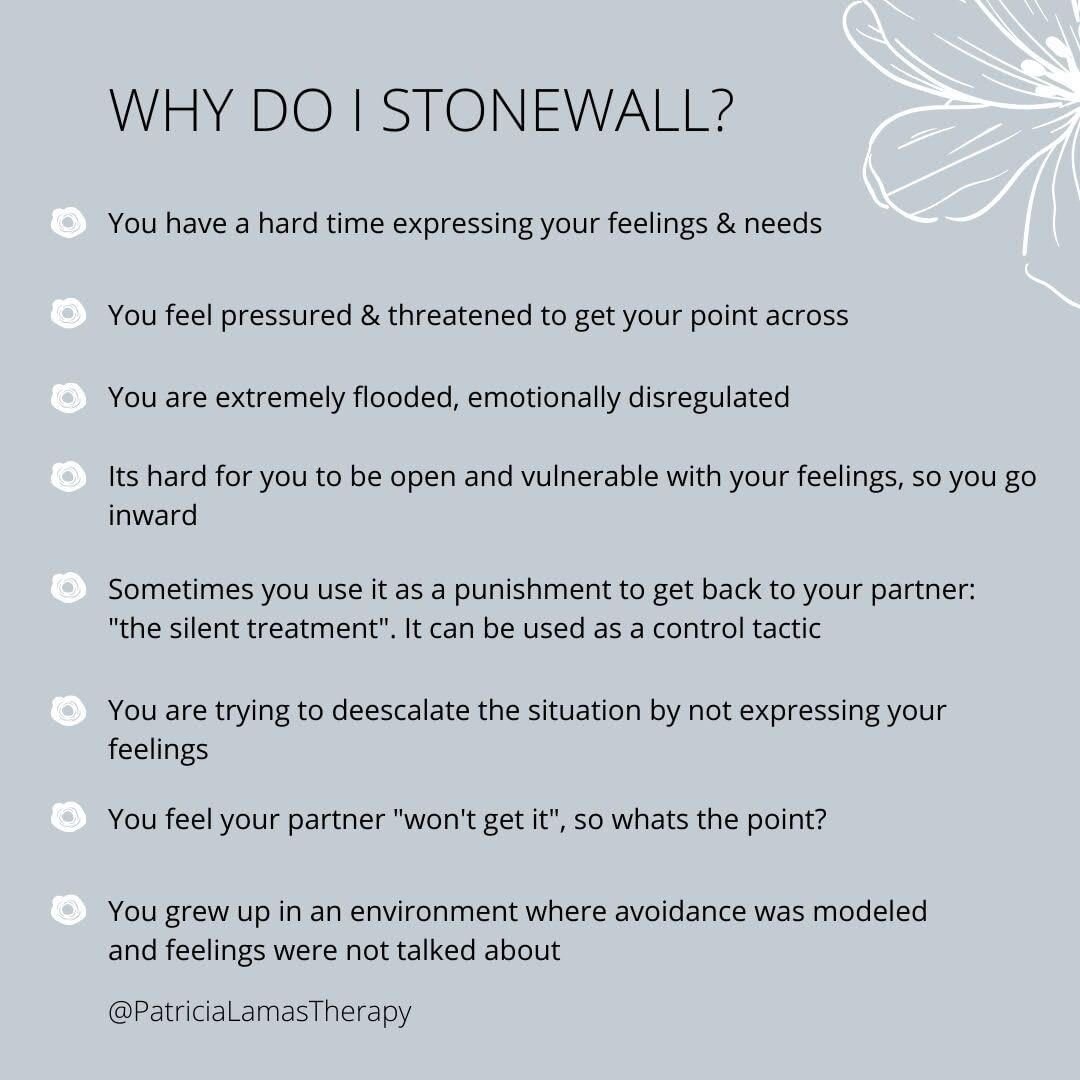

The last of the 4 horsemen, stonewalling is the tendency to just shut down or withdraw from conflict, closing ourselves off to our partners instead of engaging with them.

“Stonewalling is when the listener in a discussion becomes quiet and disengaged,” says Stensby. “Non-verbal signs of stonewalling are lack of eye contact, arms crossed, looking away, pulling away from physical contact. Basically, the person is physically in the room but mentally out of the room.”

Like defensiveness, stonewalling can be another form of self-protection—we’d rather not face our own shortcomings or the unmet needs of our partner, so we disengage. Sometimes, “this occurs when a person is emotionally flooded. They are in an emotional overload, and cannot access the part of the brain used for executive functioning. When someone is in that state, they are not able to engage in meaningful dialogue.”

The problem with stonewalling, of course, is that if we aren’t addressing conflict, then we’re never fixing the problems at the root of conflict, allowing our problems to fester. “This can be damaging to a relationship because it often creates and perpetuates a negative pattern of interaction,” says Stensby. “When the stonewalling partner disengages, this causes the other person to attempt to get the partner to re-engage or speak. They might ask more questions, or even engage in criticism to try to ‘shake’ their partner out of it, but they only further dysregulate their partner.”

The Antidote:

Stonewalling is a tricky one. Sometimes, we’re so flooded with emotion that NOT stonewalling means we might become extremely agitated and enraged. Which isn’t exactly a solution. But disengaging and withdrawing isn’t a solution either.

So instead, we should agree with our partner to take breaks during a conflict, and agree on a neutral signal for telling our partner that we need a break. According to Gottman, “this can be a word, a phrase, a physical motion, or simply raising both hands into a stop position. And if you choose a silly or ridiculous signal, you may find that the very use of it helps to de-escalate the situation.” That way, we can go take 20 minutes to cool down, and come back and discuss the conflict in a calm, collected manner.

A longer-term solution is to learn how to better handle our own emotions. Instead of engaging in defensiveness, which only causes us to sit with our own anger (“he’s being unfair! I’m the victim here!”), we need to develop the tools that help us to de-escalate our feelings. “The best way to manage emotional flooding is to self-soothe, and attempt to re-engage by using soothing touch, or an embrace,” suggests Stensby. Here are a few more recommendations for learning how to self-soothe.

HOW TO ADDRESS THE 4 HORSEMEN IN A RELATIONSHIP.

In theory, the 4 horsemen and their antidotes seem straightforward. But in practice— in a real life relationship— figuring out what to do about them is less clear. So here are a few steps to addressing the 4 horsemen in our real life relationships.

Step 1: Recognize.

Before we “fix” these horsemen, we have to first notice them. Here’s how to do that, according to Stensby:

“Does your partner get sad or hurt after you share feedback with them? If so, that’s Criticism.”

“How often do you verbalize and identify if you appreciate something about your partner? If you don’t, that could be Contempt.”

“Are you responding to your partner by trying to convince them of why you are right? If so, that’s Defensiveness.”

“Do you find yourself shutting down, walking away, or spacing out during disagreements? Does your partner complain that you won’t open up or talk about your emotions? If so, that’s Stonewalling.”

Step 2: Point them out.

Recognizing the 4 horsemen is one thing. But bringing them up to our partners seems like a scary, daunting conversation that no one wants to have.

So “the best way to point out these horsemen to our partners is to start by identifying our own role,” Stensby explains. “Talk about what we notice ourselves doing, how we feel, and then we can use an ‘I statement’ once the dialogue is opened to share how we feel when we notice these patterns happening. We can also show them an article about the 4 horsemen [editor’s note: like this one!] and ask them if they notice them in our communication. Keep the language neutral.”

Step 3: Use the antidotes.

Remember those antidotes we mentioned above? Use them. Here’s a quick refresher from Stensby:

“To Counteract Criticism: Tell your partner what you would prefer them to do, rather than what is lacking. Avoid making “you” statements or using the words ‘always’ or ‘never.’”

“To Counteract Defensiveness: Take responsibility for your actions. Own your mistakes and have self-compassion.”

“To Counteract Contempt: Practice talking about your feelings, your needs, and identifying what you appreciate about your partner.”

“To Counteract Stonewalling: Self-soothe, take a break to engage in an activity that makes you feel calm (like meditation, a walk, drink some water, listen to music), and re-engage in the discussion when you are feeling calm.”

Step 4: Get help.

Simply put, “therapy is always a great resource for identifying these horsemen in a relationship and eliminating them, if the other steps do not work,” says Stensby. “By getting early intervention, we can address these and create healthier patterns of communication in the relationship.”

But at the end of the day, we cannot force another person to change. According to Stensby, “remember that we can only control our own behavior, so if our partners don't think they need therapy and we have provided the research, information, and our own feelings already, we can’t force them. We can engage in therapy individually and start working on how we can change our responses. By changing our roles, we will change the cycles of behavior and conflict, and our partners will likely respond differently.”

HERE'S WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN A HEALTHY RELATIONSHIP.

The 4 horsemen are not impossible to work through. But “if they have been present for many years, or if they have resulted in deep wounds,” it might be very tough to overcome these obstacles, says Stensby. “When we look for what is lacking in our partner, the 4 horsemen creep in. It can be hard to take back harsh criticism and contempt, especially if it has gone on without intervention. Without any position interactions or other protective factors, it can lead to breakup.”

But according to Stensby, that doesn’t mean a single complaint or moment of defensiveness means a couple is divorce-bound. “If you are noticing the 4 horsemen in your relationship, it doesn't mean that the damage is irreparable,” says Stensby.

To gauge how healthy our relationships are, look for “a 4:1 ratio for positive to negative interactions,” says Stensby. “This means that, in order to maintain a healthy connection, we must have 4 positive interactions to counteract every 1 negative interaction. In a healthy relationship, the couple practices a culture of appreciation and acceptance. A healthy relationship requires both partners to accept each other for their flaws wholeheartedly.”

Marissa Pomerance is the Managing Editor of The Candidly. She’s a Los Angeles native and lover of all things food, style, beauty, and wellness. You can find more of her articles here.